|

|||

|

|||

|

Part 4 of 5 |

|||

| |

|||

| "I

have been made miserable by what you are keeping hushed."

|

|||

| As I embarked on my study of Lesbian Herstory, I naturally came at it with preconceptions and assumptions. One major "fact" I believed until a few years ago was that after the publication and brouhaha over The Well of Loneliness, no openly lesbian books were published until Claire Morgan's The Price of Salt and the lesbian pulp novels of the 1950s. How wrong I was! |

|||

| . |

|||

| The Big Three Virginia Woolf published time-traveling, gender-bending Orlando the same year (1928) as Hall's The Well of Loneliness. And Gertrude Stein's The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas was issued in 1933. The third member of what I like to call The Big Three, Djuna Barnes, published Nightwood in 1936. None of these novels were specifically, overtly lesbian, but in the sub-text you could read serious elements of lesbian issues. |

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) |

||

|

|

Since finding and reading The Big Three, I thought that those three oblique, subtext-rich books comprised the entirety of lesbian-related books in the Thirties. Even Q.E.D., the only work in which Stein wrote explicitly of a lesbian relationship, was not published during her lifetime. (Q.E.D. was written in 1903 and was finally brought out as The Things As They Are in 1950.) But again, there were some other outliers in the 1930s. |

||

| It's easy to find photos, book cover images, and information about The Big Three. The fame of the works and lives of Woolf, Stein, and Barnes continues on even all these years after their deaths, but two other lesser-known writers took literary chances early in the twentieth century about which most current lesbian readers are not aware. |  Djuna Barnes (1892-1982) |

||

| We Too Are Drifting In 1935, Gale

Wilhelm published We Too Are Drifting - and with Random

House, no less! A tale of drama and damnation, loathing and loss,

We Too Are Drifting explored woodcut artist Jan Morales'

life as she falls out of love with a first female lover and into a

tortured situation with another woman, whom she loses in the end.

Not a happy ending; apparently a result that lesbian readers had come

to expect. |

|||

| While writing Drifting, Wilhelm (1908-1991) lived with Helen Hope Rudolph in the San Francisco bay area. She and Rudolph were partners for over a decade, then broke up. The last 43 years of her life, Wilhelm lived with a second lover who has remained anonymous. I have turned up no photographs of Wilhelm in my research. | |||

| . |

|||

| Pity

For Women Then Doubleday brought out Helen Anderson's Pity For Women in 1937. The two characters, Ann and Judith, are filled with less loathing than Wilhelm's women in Drifting, but drama and loss still reign supreme. Lesbian literary historian Linnea Stenson says that Pity For Women is the first lesbian novel to show evidence of a resistance by the author - and characters - to the prevailing attitudes of prejudice and misunderstanding. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

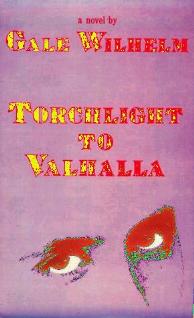

Gale Wilhelm's Torchlight To Valhalla (1938) marked the first subtle shift away from the tortured souls in the few previous novels containing lesbian themes. It might, in fact, be considered the first overt lesbian coming out novel. Young writer Morgen struggles with her identity as well as with the attention of a young male suitor only to finally accept that she loves Toni, a seventeen-year-old girl four years her junior. (I also found it interesting that for the first time in a lesbian novel, both characters are given androgynous names, Morgen and Toni. I don't know if it was intentional or not, but I liked that.) Though Vin Packer's 1952 novel Spring Fire is generally given credit as the first novel in which the two heroines experience a positive ending, the 1938 Torchlight predates it. Further research revealed that Wilhelm's novel was issued in hardback, and Packer's in paperback, so that may be why distinction is made between the two. Likely in response to the success of Spring Fire, Torchlight was also reissued in 1953 as a paperback but retitled The Strange Path. Gale Wilhelm

lived until 1991, but she never wrote another lesbian novel after

Torchlight To Valhalla. The three "mainstream"

books she subsequently wrote were critical and sales failures. In

1985, Naiad reissued both We Too Are Drifting and Torchlight

To Valhalla. Used copies of the Naiad versions can still be

gotten at various online sites. Helen Anderson never wrote any further

lesbian books either, and copies of her Pity for Women

are almost impossible to come by. |

Naiad Cover for Torchlight To Valhalla (1985) |

||

|

|

|||

Conclusion Next month we'll take a look at the war years and the 1940s. |

|||

|

|||

| If

you are curious to learn about a particular topic or have information

to share, please write to me at: Lori (at) LoriLLake (dot) com Until next time! Lori |

|||

| |

|||

| |||

| This page last updated on July 2, 2022 Go to other parts of the Lesbian Herstory Series: Part

1 Or Return to Lori L. Lake's Main Website All contents of this web site are protected by U.S.

and International copyright laws | |||

Lesbian

Fiction Herstory

Lesbian

Fiction Herstory